Can't load tweet https://x.com/vdare/status/1793136840947732588: Unknown MIME type: text/html

VDARE.com Editor Peter Brimelow: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome back.

I’m Peter Brimelow, I’m the editor of VDARE.com, and we’re coming to you, for those of you on livestream, from the Berkeley Springs Castle, which is VDARE’s headquarters, from its conference room.

Now, last night, Jared Taylor gave an interesting and very dark talk about the Confederacy, which I thought broke new ground for him.

And Fred Kelly, our lawyer, who doubles as our barkeeper and bagpiper, was going to pipe him in.

But he was on his way down from New York State with his wagon train full of children.

Take that, Great Replacement!

So he’s going to play this in honor of Jared.

(”Dixie” plays on bagpipes) (audience cheering)

To hell with Letitia James! [audience laughing)]

While I’ve been working for VDARE the last 25 years, I’ve dealt with two writers who I consider to be geniuses, or I guess genii, John, which is it?

[JOHN DERBYSHIRE] Genii. (audience laughing)

[PETER] Yeah, genii.

In the sense that, as an editor, you’re just amazed at the constant proliferation of new ideas and the fantastic imagination. And also, frankly, the extraordinary productivity. John Derbyshire writes 5,000 words every Friday.

And Steve Sailer’s column would be written in a sort of maniacal, dionysiacal frenzy every Saturday night.

So I thought it’d be a good idea if I had one genius introducing another.

John? (audience applauding)

[DERB] Thank you, Peter. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen.

I’m glad to be here in one piece.

I had this nightmare when Peter started talking about ”it is finished” and VDARE.com was going to have to wind up, that at this event, he might have all these speakers line up at the end and commit collective seppuku. (audience laughing) With Jared Taylor advising us as to the correct procedure!

(audience laughing) But apparently not, we’re still here.

And as I told Peter, when he posted that deeply pessimistic notice on Good Friday, crucifixion was not actually the end of it. It was followed by a resurrection.

So, Steve Sailer. Yes. I’ve known Steve Sailer’s name since we were both writing for National Review in the 1990s. I didn’t know him in person until much later, but I liked his stuff right away. It’s very striking, the things that he brought up.

One piece of his that stuck in my mind was, this was the mid-90s, the difference between lesbians and homosexuals, and he went through it all with good quantitative data [Why Lesbians Aren’t Gay, National Review, May 30, 1994].

![]()

I thought, that’s excellent.

And at the time I was doing physical training in a local gym run by two ladies. And one of them used to train me and she used to chat a lot about her life and what she’d done at the weekend. And I started to notice it was ladies this and ladies that.

At last I summed up the courage to ask her, I said, ”Jennifer, when you say ladies, is that like ladies, ladies?” And she rolled her eyes and said, ”John, how dumb are you? [audience laughing] What do you know about me? I was in the Army, I played golf, I ride a motorcycle.” Hello!

And that sort of keyed in with what Steve had written about so well.

And then I joined Steve’s email list, we used to call it listserv, this is when the internet was new at the end of the 90s, which was a private email group where we just emailed each other.

And there were a lot of names on that group, I won’t name them in public, because it might not be good for them, but there were names there that have since attained considerable fame and fortune, in one case is Stinking Rich.

He was only a college student when he was on the HBD list, this was the HBD list, Human Biodiversity.

So I got to know them, now I don’t quite know why Steve invited me onto the HBD list, perhaps he’ll tell you.

![]() But there was a lot of fun.

But there was a lot of fun.

And then in 2009, another 10 years on, I published a book called We Are Doomed, Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism.

I thought conservatives had got much too happy clappy, and it was time to assert a little reality.

And at the very end of my book, I had a page of acknowledgement, such as you do with a non-fiction book, and I acknowledged my editor and my publisher, and my agents, and then I added a paragraph, which I’ll just read to you.

And then I added this.

In writing this book, I have borrowed pretty freely from the online writings of my friend Steve Sailer. As well as some ideas, my borrowings include entire phrases—Steve is a master of the memorable phrase.

”Invade the world, invite the world, in hock to the world” is one of his coinages.

I took ”Yale or jail” from Steve, thinking it was his, but he tells me he got it from education reformer John Gardner.

I am sure there are other Sailerisms in my text. I have used some of Steve’s data, too. He is a great quantitative journalist: I once heard him describe himself as ”the only Republican that knows how to use Microsoft Excel” (which may very well be true).

In a sane republic, Steve would have some highly-paid position advising the government, or a professorship in social science at some prestigious university.

In the nation we actually live in, Steve can only be a guerrilla intellectual, emerging from the maquis now and then to take a few sniping shots at what George Orwell—Steve’s greatest hero, and mine—called ”the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.”

So that’s me and Steve, and I continue to be a devoted follower of Steve and all he writes.

And as I said, he is one of the great quantitative journalists, a category of employment which is badly in need of some kind of recruiting drive. We don’t have enough good quantitative journalists.

Here is the best one, Steve Sailer.

[Bagpipes play] [Applause]

Steve Sailer: Thank you very much, Fred. That’s from, probably, my favorite movie, The Man Who Would Be King. So I think Fred’s got that figured out just right.

[VDARE.com Editor Peter Brimelow writes: I’ve come to realize that not everyone knows this tune, famously sung by Michael Caine with the Victorian hymn lyrics in The Man Who Would Be King, is actually Thomas Moore’s great Irish nationalist song The Minstrel Boy. I like it because these lines bring Steve to mind:

”Land of Song!” said the warrior bard,

”Tho’ all the world betrays thee,

One sword, at least, thy rights shall guard,

One faithful harp shall praise thee!”]

Steve Sailer: Alright. So I want to thank everybody for coming. And I’d especially like to thank Peter for hiring me as a VDARE columnist 24 years ago. So I’m now on a book tour promoting my anthology called Noticing. And it’s kind of my greatest hits collection. It’s selling here.

![]() It’s available online from Passage Press.

It’s available online from Passage Press.

Paperback is a not unreasonable $30.

And of course the hardcover is, well, is lavish in all regards, including the price they set for it at $395.

But there are people who bought them.

So I’m going to read the last chapter from Noticing. It’s called What If I Am Right?

And I wrote it over the last few years and finished it last summer.

And it’s probably a little more pessimistic.

I may be more optimistic now 9, 10 months later than when I wrote it, in part because of these kinds of warm welcomes.

What if I am more or less right about how the world works?

What if my way of thinking is in general more realistic, insightful, and reasonable than the conventional wisdom?

What would that imply?

First note though that I dislike thinking of my system of noticing as an ideology that demands certain policies. I don’t propound Sailerism. I lack the ambition and the ego. I am by nature a staff guy rather than a line boss. I’ve never especially wanted to be a George W. Bush–like decider. Instead I like being a noticer. I'd rather explain to the public the trade-offs. Indeed, I most of all want to show people how you can make use of my techniques for figuring things out for yourselves.

My basic insight is that noticing isn’t all that hard to do if only you let yourself. The world actually is pretty much what it looks like, loath though we may be to admit it.

My main trick for coming up with enough insights to make a living as an unfashionable pundit for a couple of decades has been to assume that private life facts—what we see with our lying eyes—and public life facts—what the scientific data tell us—are essentially one and the same. There is only one reality out there. We don’t live in a gnostic universe in which there is a false reality of mundane cause-and-effect and a horrifying true reality in which unnoticeable racism determines all fates.

In contrast, most commentators of the 21st century assume that issues of daily life, such as deciding where to live, are of a lesser, more sublunary realm than the high public issues such as the sanctity of Black Lives Matter. So the unfortunate facts that they prudently observe when making real estate choices for their families about safe neighborhoods and ”good schools,” couldn’t possibly have any relevance to the great topics of the day that they discuss in the media. Only vulgar lowbrows would confuse these two vastly different domains of being.

Progressives assume there is a “crime” problem that they try to sidestep with their money, and a “Social Justice” problem that they try to solve with other people’s money by imposing upon the rest of society the opposite of what they do in their own lives.

In truth, you don’t need unfalsifiable dogmas like “systemic racism” to explain everyday facts like why blacks on average are relatively better at playing cornerback than playing center in the NFL. Biological and cultural differences, nature and nurture, explain these and countless other patterns. Indeed, trying to figure out how nature and nurture intertwine in modern America is one of the great challenges of the examined life.

Public intellectuals should try it. It’s fun.

When it comes to human behavior, there mostly aren’t systematic differences between what you see with your own eyes and what The Science says.

Instead, there’s a continuum between anecdote, anec-data, and data. For instance, if you can recall several examples suggesting a pattern, you might well be able to find a large-scale dataset against which to test your supposition.

Conversely, if there’s a strong statistical pattern in the numbers, you should be able to come up with vivid real-life examples of it.

If you can’t think of any, maybe there’s something wrong with the statistically esoteric analysis. That I assume all truths are connected to all other truths helps explain why my column often seems to end somewhat abruptly and arbitrarily, much to Peter’s dismay over the years. Typically, I don’t act as if I’ve reached the conclusive end of a topic, because from my perspective, there is no conclusion, just an endless network of cause and effect. So instead, I tend to merely knock off around dawn when it’s long past time to go to bed.

I’d like to tell myself that I should just keep coming up with more ideas that are, in declining order of importance to me, true, interesting, new, and funny.

Eventually, people will notice how much better my approach to reality has been than that of the famous folks winning the MacArthur Genius Grants and try to figure out for themselves how I do it so they can too. Or at least that’s what I hope.

On the other hand, when I wrote this in 2023, it struck me that, you know, public discourse has just gotten stupider and more socially self-destructive over the course of my three-decade career.

Maybe that’s partly my fault.

What if I just kept my mouth shut and instead of challenging popular pundits to be honest and intelligent, I’d let them work it out for themselves?

After all, people who know me tend to find I’m an okay guy. People who don’t know me tend to hate me.

Thus, when I point out the facts, I’m often greeted with incoherent anger centering on the presumption that I must be a bad person for being so well-informed.

When I started writing my views were edgy but not unknown.

Intellectually, I’m basically an heir to the debates in the early 1970s among data-driven social scientists, with me being closer to the domestic neoconservatives like James Q. Wilson and Richard Herrnstein. But I also admired liberals like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, socialists like Christopher Jencks. So, what’s changed since the 1970s?

Basically, all that has happened is that the data have continued to pile up against the establishment view. I find it an exaggeration to say that the Left totally dominates the content of the social sciences today. I have been a human sciences aficionado for the past half century, and I haven’t seen much decline in the number of findings supporting my general worldview, in part because I constantly adapt to new findings, but also because new advances have typically validated the best old research. For example, the genetic revolution of the 21st century has mostly vindicated the best scientists of the second half of the 20th century.

Granted, journalists tend to not grasp that the current dogmas like ”race does not exist” are obfuscations to keep geneticists from getting cancelled by know-nothings. But if you read the scientific journals carefully, you’ll see what’s what.

Yet, instead of changing minds, the passing of the years and the accumulation of vast amounts of empirical evidence have only made the dominant discourse ever more absurdly antiquarian.

For example, the failure of property values to boom in black neighborhoods in the 55 years since redlining was legally abolished has not made it more acceptable to point out that if blacks want higher home values (which it’s not clear that they all do) they should work harder on being better neighbors. Instead, we hear ever more often about FDR’s redlining as if that’s what’s really driving the real estate market nearly a century later.

My approach in explaining human society has been to follow the general line of Occam’s Razor that the simplest feasible explanation is less likely to be contrived for political purposes than a more complicated rationalization based on what I call Occam’s Butterknife.

For example, home values today tend to be determined by current crime rates and school test scores, not by FDR’s malevolence 85 years ago.

And as more data continues to accumulate over the decades, my depiction of the way the world works seems to have a better track record than more fashionable theories.

Now, it’s not that I’m infallible. Still, A, I like to argue, and B, I don’t like to lose. So I look hard for good arguments and the strongest evidence so I can win. And when I lose, rather than double down, I try to change my mind.

I would encourage intellectuals to subscribe to a form of vulgar Hegelianism in their thinking that I found very useful.

If you hold the thesis for what seems like good reasons and somebody counters with a well-argued, well-evidenced antithesis, you have three options.

- The most common is to reject the antithesis out of hand.

- The most dramatic is to convert to the antithesis.

- Probably the most productive, even if it’s the hardest, is to look for a synthesis. Make sense of both your thesis and the other guy’s antithesis.

That was a really hard sentence to read.

I felt like Daffy Duck trying to read that.

For example, oh-oh, I see it again.

I’ve done it again.

- Thesis: a racial group is a taxonomical subspecies.

- Antithesis: a racial group is a biologically non-existent social construct.

- Synthesis: a racial group is a partly inbred extended family and thus like all extended families, it’s a little hard to figure out where the boundaries are.

You have a different extended family for whom you send a Christmas card to versus whom you invite to Thanksgiving dinner.

So, what if I’m right?

How would the world look different?

Well, it wouldn’t. I’ve taken pains to make my worldview correspond with how the world actually appears to be.

What policies are implied by my realistic view of humanity?

To my mind, nothing terribly new. In general, we need rule of law. We need equal protection of laws and other old-time principles.

For example, the fact that African-Americans have a high crime rate for whatever combination of reasons of nature and nurture suggests that they need law and order, perhaps even more, not less, than the rest of Americans. Now, as you may recall, the establishment tried in 2020 to reduce the rule of law during the Racial Reckoning. The result of less policing was that in 2021, blacks died by both homicide and traffic fatalities 40 percent more than in 2019.

An enormous, lethal catastrophe unleashed by all the well-established thinkers of America and people who didn’t stand up to them.

The usual responses I’m given by my critics are either, one, my findings are rejected by all experts as completely untrue, or, two, everybody already knows that what you’re saying is true. They just don’t want to talk about it.

Among those who assert the latter, I’m told that we shouldn’t mention the truth because either, one, the facts have no possible policy implications, or, two, the facts have overwhelmingly horrible policy implications, such as the logical necessity of reimposing slavery or committing genocide.

The former strikes me as obtuse and the latter as evil or insane.

When I tried to think through the policy implications that would flow from honest public discussion of American realities, it strikes me that it would be useful if more people knew more about what they were talking about. Knowing the facts doesn’t prove one set of values is better than another. That’s what politics is for deciding.

But it can help you avoid making things worse than they have to be, as we saw in 2020.

But what if noticing became widespread?

To explore this question, I’m going to focus on one controversy, one where I actually had some impact on the upper-end conventional wisdom.

I wound up largely winning the debate and changing opinion on a topic called the gender gap in Olympic Track.

The study of track and field results is very interesting for sports in general and reality because it’s just so cut-and-dried, there’s so much data, and it’s much easier to work with than just about anything else.

Back in the 1990s, a majority of the American public and media was under the impression, according to surveys, that in the near future, a generation away or so, that women runners in the Olympics would be running just as fast as men runners.

This was kind of the conventional wisdom at the time.

And it sort of made sense in that in the 1970s and 1980s, the gender gap between men runners and women runners was closing.

And if you just projected out the convergence, at some point in 2002 or something like that, they’d catch up.

But as I pointed out in 1997, what was actually going on was that the gender gap had been widening since the 1988 Olympics, and two things happened at the end of the 1980s.

One was there was a huge scandal when the Canadian runners set the world’s record in the 100-meter dash and was immediately discovered, just basically it was 98% steroids by that point.

And the next year, the Berlin Wall came down and the famous East German women’s Olympic team was no more.

And what was going on was that women were getting a bigger bang for the buck from the synthetic variants of masculine hormones, so they were able to up their speeds more without getting caught by the crude testing of the time.

Then after 1988, there was a little bit more testing, you know, it’s really infallible today, but then the gender gap kept getting bigger, and now it’s been stable for the last, you know, third of a century or so.

So for a number of years after I published this article [Track & Battlefield, National Review, December 31, 1997], I’d see articles pushing the 1990s consensus that we’re going to have convergence Real Soon now.

And if the person writing that seemed like, you know, that they were actually interested in science, I’d send them my article and go, ”No, it was just steroids in the 70s and 80s.” And sometimes they’d even write back and go, ”Oh, yeah, you’re probably right.” And over time I stopped seeing prognostications of convergence among all but the most ill-informed in the press.

So, what were the dire side effects of people learning the truth about, yeah, there’s kind of a permanent natural gender gap in how fast men and women run?

Did high school girls stop running in despair?

Were women’s sports banned?

Nah.

The main effect so far as I can tell has been a beneficial one for women’s sports.

All right, 2013, I noticed the New York Times is really pushing transgenderism, and they’ve got, they run this huge article about an ex-man named Fallon Fox, who’s an MMA martial artist and wants to get paid to beat up women.

And he’s not being, or she now, is not being allowed to beat up women for money, and this is just the worst discrimination ever.

I went, ”Holy cow, this is the big thing they’re planning to come after gay marriage.”

And yeah, that’s what happened.

You know, the world went crazy in that regard over the last decade.

But the good news is that today, and this doesn’t apply to the Biden administration, of course, but in general, society over the last few years has started to go, ”No, actually we don’t want men in skirts destroying girls in high school sports. We don’t want them beating up real women.”

And most sports are saying, ”No, we’re not going to do this. This is crazy.”

And one reason for that is that the autogynophilia fetishists can no longer argue, ”Well, you know, everybody knows that women are converging with men, so if us female impersonators jump the gun just a little bit, you know, that’s no big deal, because we all know that there can’t possibly be a gender gap due to nature.”

Well, actually, people do sort of know that now, and they’re okay with it, and if they’re not in the White House, yeah, they want to, like, preserve women’s sports the way they were, and not let them get destroyed by cheaters with bizarre fetishes.

So, maybe I’m over-optimistic, but that strikes me as a likely model for what would be the result of more of my ideas coming to be accepted as sensible.

Neither utopia nor apocalypse, but some improvement in the rules and discourse.

And perhaps most valuably, various new, even worse ideas that we haven’t yet imagined would be headed off at the pass.

Okay, I wrote in 2023 that, all right, that may not be the most decisive way to conclude my book, but then perhaps then I was merely knocking off around dawn because it’s time for bed.

Ultimately, I believe that the truth is better for us than ignorance lies or wishful thinking, and in any case, it’s a lot more interesting.

Thank you very much.

[applause]

[PETER] Thanks, Steve. Wow, he’s tall. Okay. So let’s go to questions. Where’s the microphone? Oh, thanks very much.

If you can go over to the microphone and ask the questions.

Thanks very much.

[QUESTION] Hey, thanks, Steve.

I’m just wondering, there’s I think a sense lately, our ideas are getting out there a bit more.

I think social media has a lot to do with it.

I know your following on Twitter/X has grown substantially recently.

But then, you know, I saw a survey the other day that said, you know, they polled 500 Americans and the most taboo topic to them was race and IQ, ranked above, like, you know, discussions of morality of incest, all these kinds of controversial things.

And, you know, I guess the other perspective is, you know, there was a time when Charles Murray’s thesis has been discussed on pretty popular mainstream shows.

So I’m just wondering, you know, with all your experience, what’s your sense of that?

You know, how optimistic are you right now about these ideas getting to a bigger audience?

[STEVE] Yeah, I think you’ve basically hit it very well that, yeah, there are reasons for optimism.

There are green shoots of a new spring intellectually.

But also, you know, I’ve been doing this for a whole long time and I’ve had friends who are like calling me up, you know, in 2002, 2009, 2015, and going, oh, Steve, I just saw something. I think it’s a turning point.

And not really. It didn’t happen.

So, yeah, I think you’ve got exactly the right attitude, which is there’s hope. But there are also excellent reasons for skepticism.

[QUESTION] Hi.

Do you like sometimes read, let’s say, how should we put this, more widely read op-ed people?

And I read sometimes I read their stuff and I go, wow, that sounds a lot like Steve Sailer. Do you think this is just a case of great minds think alike or do you have any direct knowledge that they’re cribbing from you?

[STEVE] I mean, I don’t know if a lot is the right word.

There are quite a few of the leading opinion journalists who have come in contact with my ideas.

And, you know, it’s not uncommon to find the bright ones doing something where it’s basically obviously inspired by something I wrote.

And then they changed the direction slightly to not get in trouble.

And it’s quite good what they’re saying.

You know, there’s a prominent Substack pundit who’s been around for a couple of decades.

And it’s kind of like, all right, if I write something about hot-button topics of race or sex, then, you know, a week later, he might have something that follows the same logic, but it’s about something like age differences that aren’t that controversial.

But he’s making a good point about he’s got some public policy issue or something like that.

Quite a few of the people who emerged in the blogging era of the early 2000s have followed me.

I’ve had this kind of strange influence on them. I sort of became the Lord Voldemort who cannot be named.

I don’t know. I’ve never quite understood that.

But that that’s the way the world worked for the last 20 years.

[QUESTION] I’m not surprised to hear that you and John Derbyshire are fans of George Orwell.

What do you think is particularly important about what we should learn or know about Orwell’s views?

What Orwell is saying to you today?

[STEVE] I’ve always been very fascinated by the appendix to Orwell’s 1984, where he explains how Newspeak works.

![]() And one point was that in the party in 1984 is decreasing the number of words because there are all sorts of crimethink topics that they don’t want people thinking about.

And one point was that in the party in 1984 is decreasing the number of words because there are all sorts of crimethink topics that they don’t want people thinking about.

And if they don’t have a word for concepts, it’s harder for them to think about. They have to sort of mentally wave their hands around a lot and they can’t.

And it’s especially hard to communicate to somebody else.

So the end of the appendix is—Orwell quotes the most famous part from the Declaration of Independence.

He says that when Newspeak is finally completely mature, none of these, none of the concepts of Jefferson will be expressible in the Newspeak language.

The only word that will apply is Crimethink.

So just to give you an example, basically, there’s a lot of things that the press tries to keep you from having a word for, a name for.

We were talking at dinner about how in 2015, German Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to open the gates of Germany to let in a million military-age marching Muslims. And that’s actually had a huge impact on Europe.

European politics are like, no, we don’t want to do that. But in the United States, practically nobody can remember it because the press made sure never to give a name for it.

And, you know, I suggested based on baseball history from a game in 1908, Merkel’s Boner. That didn’t go over.

But Merkel’s mistake is alliterative, all sorts of things like that.

And I think in a lot of Europe, people would recognize, oh, yeah, that was a thing that was shocking when it happened.

But it was also sort of completely logical under the concepts that dominated European politics a decade ago.

But in the U.S., the press has managed to keep people from having a name for it, so it kind of gets lost in the blur of events.

[QUESTION] Yeah, I guess you realize that George Orwell was really a socialist.

And his views on the totalitarian nature of socialism, I think, transcend these, these probably artificial differences among, among European people of European heritage.

And I would like your thoughts on that.

[STEVE] Yeah, I mean, I mean, my thoughts are, I’ve always argued that, you know, if we, if we had an awareness of human biodiversity and human cultural diversity, and we were allowed to talk about it, would that be the end of the world?

No, we'd just have better informed politics.

I mean, some people would say, would therefore argue for an American rightist, liberal libertarian economy, and other people would argue for a John Rawlsian–type Swedish welfare state.

What I suggest is, and those are reasonable sides, and what I would suggest is that, you know, that you can go with either argument, but if you go for the Swedish welfare state, you really can’t let the whole world in.

You know, 94% of the world isn’t American.

So, and actually even in Sweden, that concept has been catching on in the 2020s.

In the U.S., it’s still kind of verboten to think about that.

But there is a certain amount of progress being made.

[QUESTION] Steve, you talked about the quotas of Jewish students in the 20th century, early 20th century.

They were restricted at Harvard, etc.

My question is, why didn’t Jews form their own university, like Mormons did with Brigham Young, Irish did with Notre Dame, they could call it, like, Benjamin Disraeli University, like why don’t they say, hey, these Anglo-Saxons, they won’t let us in, we’re going to compete with them, we’re gonna build a better university.

[STEVE] Yeah, I mean, that’s a really interesting question.

There was one, Brandeis, and it was definitely a response to quotas at Harvard that were imposed in 1922.

And it was founded right after World War II. It probably would have become a world-famous university, the original plan was to call it Einstein University, with Albert Einstein as a president.

But then in the 50s Harvard said, actually, we want as many smart people as we, we want more than we’re getting right now.

And so they kind of undercut Brandeis.

But it’s an interesting question because, you know, Jews were extremely enterprising at founding hospitals, founding country clubs.

But there’s something about universities that is, just, the older they are, the more popular, more prestigious they are.

So colleges like Harvard and Yale are just enormously ancient by American standards.

I mean, when I was in high school, people said, Harvard and Yale, you know, they’re the Pan Am and TWA of colleges.

Well, everything else changes, but not Harvard and Yale

So why is that?

I don’t really know.

But I mean, I look at lists of prestigious liberal arts colleges, and yeah, probably, F. Scott Fitzgerald could have come up with the same one in the 1920s.

It’s just something that’s extremely traditionalist.

So it has good sides and bad sides as well.

[QUESTION] If Noticing is a skill, besides giving someone your book, how would you teach somebody to be a Noticer?

[STEVE] Yeah, I mean, it’s basically, probably the person who had the biggest influence on me is my wife.

When we got to know each other in the 80s, I was a pretty standard conventional sort of Reaganite conservative.

I was interested in topics like, you know, Federal Reserve policy, things like that.

And she was not interested in Federal Reserve policy.

What she was interested in were all the people around us and the decisions they’re making and what incentive structure they face and why they’re making these decisions.

And I was like, Oh, wow, this actually is more interesting than the Federal Reserve.

And so my thought is basically to apply your practical reasoning to what you see every day in the world.

And to, you know, the things you read about on the opinion page of the newspaper.

And yeah, that’s basically that it’s all connected.

And, you know, it’s not two different things.

[PETER] Steve, we asked on Twitter for a couple of questions.

And one of them is... This should take some time! What are your predictions for the USA in 2050?

[STEVE] First, I’m not a big forecaster.

The world has actually made some progress on forecasting techniques.

A Professor named Philip Tetlock has actually tested very rigorously and recruited people who were good at forecasting world events over the next 12 months.

He has a super forecaster contest each year and people are very good at it.

Not, not everybody, but he’s found, you know, a hundred people were consistently much better than average.

And I mean, I’ve talked to people who are catalog super forecasters and one point they make is, yeah, it’s kind of a lot of work.

For example, there’ll be a question like on December 31st of this year, what will be the opinion of the Philippine government toward Chinese actions in the Spratly Islands?

And I’m like, that could be the world’s most important issue at some point, but I’m not going to think about that.

That’s boring.

And so, yeah, it’s been a lot of time studying this kind of stuff and then changing it.

So as a forecaster, I haven’t noticed I was very good at, I was never very good at forecasting the Federal Reserve’s actions.

There are people who make a lot of money doing things like that.

So I try to be sort of a contemporary historian and then I try to like go, oh, here’s what’s going on right now. And this is part of a trend that’s been emerging for a long time.

So let me make some forecasts.

One is I’m going to say, something really controversial, which is, yeah, I don’t think we’re going to see a complete collapse of the United States.

![]() I think things are kind of going to kind of bump along the way they are now and just kind of deteriorating slowly.

I think things are kind of going to kind of bump along the way they are now and just kind of deteriorating slowly.

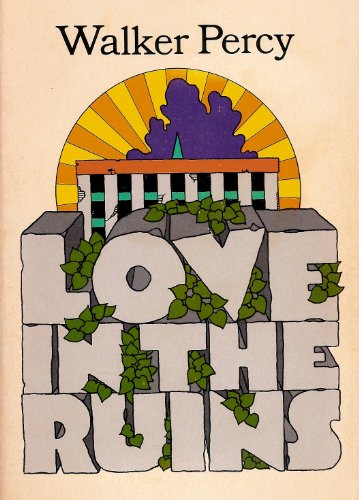

The semi-dystopian book I would suggest was a 1971 novel by the Southern writer Walker Percy called Love in the Ruins. It said in the near future in 1983 United States, it actually seems a lot like the 2020s America.

Things haven’t collapsed.

Everything’s kind of going on.

It’s just everything’s slightly more deteriorated and kind of poorly run.

And it’s just not as good as it was in the past.

And yeah, that’s what I think is going to happen.

I’ll say that things will bump along not as good as they could be.

But, you know, there’s a whole bunch of issues that I can’t even begin to conceive of, like, what’s the impact of Artificial Intelligence?

I’ve been hearing about Artificial Intelligence.

I was hearing about in the job in the 1980s, the 1990s, the 2000s.

At some point, I lost interest in it.

And then all of a sudden, it sort of happened after my validly kind of pooh-poohing it for decades.

All of a sudden, wow, this stuff is amazing.

What’s the impact of it?

I don’t know.

So I’m just going to leave it at that.

PETER BRIMELOW: There’s a final question here. What is Steve’s favorite dinosaur?

STEVE: I do have a strong opinion on that.

And yeah, it is characteristic.

My favorite dinosaur is the Brontosaurus, which got renamed the Brachiosaurus.

![]()

And I don’t like the Brachiosaurus, but I definitely like the Brontosaurus.

Steve Sailer (Email him) has writings available on VDARE.com, on Unz.com, on TakiMag.com, on Twitter @steve_sailer, and in book form in

But there was a lot of fun.

But there was a lot of fun. It’s available online from Passage Press.

It’s available online from Passage Press. And one point was that in the party in 1984 is decreasing the number of words because there are all sorts of crimethink topics that they don’t want people thinking about.

And one point was that in the party in 1984 is decreasing the number of words because there are all sorts of crimethink topics that they don’t want people thinking about. I think things are kind of going to kind of bump along the way they are now and just kind of deteriorating slowly.

I think things are kind of going to kind of bump along the way they are now and just kind of deteriorating slowly.