![]() Like many of you, I’ll spend this Halloween bingeing on my favorite horror movies. Tops among them: 1968’s The Devil Rides Out, a Christopher Lee vehicle based on the novel of the same name. It’s about three friends and their spiritual battle with an evil magician. The story subtly reveals the old-time Anglo-American conservatism of author Dennis Wheatley, a novelist-turned-British agent deeply involved in hugger-mugger planning against the Germans in World War II. He was a conservative, a race-realist, and an unabashed defender of the Christian civilization that formed him.

Like many of you, I’ll spend this Halloween bingeing on my favorite horror movies. Tops among them: 1968’s The Devil Rides Out, a Christopher Lee vehicle based on the novel of the same name. It’s about three friends and their spiritual battle with an evil magician. The story subtly reveals the old-time Anglo-American conservatism of author Dennis Wheatley, a novelist-turned-British agent deeply involved in hugger-mugger planning against the Germans in World War II. He was a conservative, a race-realist, and an unabashed defender of the Christian civilization that formed him.

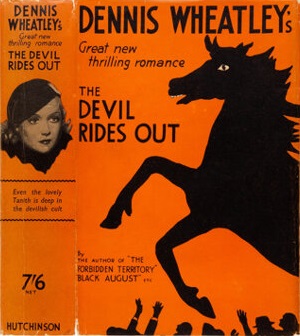

Published in 1934, The Devil Rides Out combines fast-paced action in electric-age London with the occult, foreign intrigue, and elements of imperial adventure. It’s the story of exiled French aristocrat Duc de Richleau, an American adventurer Rex Van Ryn, and their friend Simon Aron. Their enemy is Mocata, a necromancer. This is same trio of heroes as Wheatley’s 1933 debut, the anti-Soviet espionage thriller, The Forbidden Territory.

![]() Richleau, a cosmopolitan of great learning who uses white magic to defeat Mocata, is something of an early hippy, or at least a believer in the slogan of “CoExist.” “Most people agree now that Buddha was a sort of Indian Christ,” Richleau says to Rex, “a Holy Man, and no doubt he had some sort of power granted to him too.” Richleau’s view of the world’s religions stems from his belief in what he calls the “Invisible Influence,” the unseen sensory vibrations supposedly common to all cultures. His nearly Gnostic enlightened knowledge makes Richleau a formidable foe to Mocata, also well-versed in white magic.

Richleau, a cosmopolitan of great learning who uses white magic to defeat Mocata, is something of an early hippy, or at least a believer in the slogan of “CoExist.” “Most people agree now that Buddha was a sort of Indian Christ,” Richleau says to Rex, “a Holy Man, and no doubt he had some sort of power granted to him too.” Richleau’s view of the world’s religions stems from his belief in what he calls the “Invisible Influence,” the unseen sensory vibrations supposedly common to all cultures. His nearly Gnostic enlightened knowledge makes Richleau a formidable foe to Mocata, also well-versed in white magic.

The satanist Mocata is fat, bald, and slimy. He and his cult seek to make Simon a member, and in one incredible scene on the Salisbury Plain, the site of Stonehenge, nearly initiate him during a ceremony when they raise the fearsome demon Baphomet. Only a golden crucifix thrown by Richleau stops the Evil One from claiming Simon’s soul. The model for the slug-like Mocata, by the way, was the occultist and sexual deviant, Aleister Crowley [The Great Beast 666: who was Aleister Crowley?, by William Whyte, NationalTrust.org.uk].

The novelist James Hilton, who wrote Lost Horizon and Goodbye, Mr. Chips, called The Devil Rides Out “the best thing of its kind since Dracula.” But beyond the classic tale of Light against Dark, the book is implicitly political.

Richleau’s statements about race, common to men of his time, would get him permanently banned from polite society today. Richleau tells Rex that the Malagasy of Madagascar, for instance, are an Afro-Polynesian mix (“Austronesian,” these days), “which are said to have inherited the worst characteristics of both races.” Richleau wrongly says that voodoo comes from Madagascar rather than West Africa, but he also elaborates on the differences between Europeans and other races vis-à-vis spirituality and history: “Were it otherwise, the white races [less susceptible to voodoo, etc.] who have neglected spiritual growth for material achievement … would never have come to dominate the world as they do today.” This was uncontroversial in 1934, when the British Empire, as well as the Dutch, French, Belgians, Italians, Portuguese and even the Americans, had colonized most of the non-white world.

The multiracial, multicultural element of Mocata’s coven is also noteworthy. Besides representing the idle rich—parallel to our own class of elite pedophiles and wealthy diabolists—Mocata’s followers include a Chinese mandarin, a French countess, an Midwestern American heiress, a one-armed Eurasian, and a Malagasy witch doctor. They are the negative versions of Richleau, Rex, and Simon. While the devil worshippers represent the degenerate rich, the unassimilated immigrant, as well as the old pagan enemies of Christendom, Richleau, Rex, and Simon represent the opposite virtues: masculinity, loyalty, faith. Richleau is a Frenchman who embodies the best of the old aristocracy; Rex is the New World whiz kid with combustible American energy; Simon is a fully-assimilated English Jew. The victory of three friends can be read as a triumph for Western identity.

![]() All this tracks with Wheatley’s background and personal politics. His life, wrote biographer Phil Baker in The Devil is a Gentleman, was as spectacular as his fiction.

All this tracks with Wheatley’s background and personal politics. His life, wrote biographer Phil Baker in The Devil is a Gentleman, was as spectacular as his fiction.

Born in 1897 in London, Wheatley grew up solidly middle class. The family’s limited wealth came from their wine business, Wheatley & Son. His father viewed Wheatley as a malingerer, evidence for which can be found in Dennis’ expulsion from Dulwich College when he was 12. His troubles included wine and women; he was uninterested in formal education. He joined the Merchant Navy, and after a brief spell aboard the training ship H.M.S. Worcester, went to Germany to learn the wine business. He failed and returned home after six months.

The Great War provided Wheatley with the adventure he craved. In 1914, he was commissioned an officer in the Royal Artillery Company. Wheatley not only trained on Salisbury Plain, which would later figure prominently in The Devil Rides Out, but also met the convivial conman Gordon Eric Gordon Tombe, the son of a Protestant Irish clergyman and a bon vivant who dazzled Wheatley with tales of sex and black magic [Stranger than fiction, by Peter Sheridan, Daily Express, August 28, 2012]. Wheatley’s turn in France during The Great War lasted from August 1917 until May 1918, when he was so badly gassed that he was sent back to England to recover.

Wheatley returned to the wine business, selling wine, rare brandies, and upmarket liqueurs to the Duke of York (future King George VI) and other members of the British royal household. Married twice, he suffered like everyone else because of the Great Depression. But unlike many, he wrote fiction to make money. The Devil Rides Out was Wheatley’s second and most popular novel.

Wheatley was an ardent patriot and supporter of the British Empire. He loathed both Soviet Communism and German Nazism. During World War II, Wheatley joined the Royal Air Force Reserve. He soon became a member of the London Controlling Section, which concocted deception plans to fool the Germans on D-Day and beyond. Wheatley excelled and received a Bronze Star from the U.S. for his work.

He befriended Royal Navy Reservist and James Bond creator Ian Fleming, who likely imbibed not only Wheatley's many spy novels but also took notes from Wheatley the spymaster as well. Wheatley also befriended, by the way, Maxwell Knight, the former British Fascist and possible inspiration for Fleming’s “M.”.

After the war, Wheatley wrote espionage potboilers. Arguably his best composition was Letter to Posterity, a private manuscript composed on November 20, 1947. Written following the marriage of the future Queen Elizabeth II to Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark (the current Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh), Letter to Posterity lays bare Wheatley’s reactionary politics. A believer in the unique genius of the British, Wheatley nevertheless heaped scorn on the representative democracy practiced in the Anglo world. He disdained the notion that “all men are created equal,” and he similarly despised the democratic socialism of Britain’s postwar Labour government.

Wheatley believed the labor reforms of the late 1940s would lead to national bankruptcy, as British workers would work less and expect more benefits. He thought egalitarian education would “undermine the vigor of the race.” Democracy was the faith of the bovine herd. To defeat it and its inevitable Communist outcome, Wheatley told his readers to rebel against the modern world, to believe that “some have imagination and abilities far above others.” To stifle the innate creativity and genius of the most talented and determined is to strangle the whole race, Wheatley believed.

Less than a year later, the MV Empire Windrush unloaded its first collection of West Indian workers. They were meant to help with the postwar labor shortage, but were, in fact, the first wave of unexpected British passport holders from the colonies who were to make Britain their home. Within two generations, immigrants from the West Indies inspired Enoch Powell's “Rivers of Blood” speech in Birmingham. A half century on, Pakistani immigrants orchestrated massive rape gangs in working class cities designed to humiliate white and non-Muslim girls.

Needless to say, Wheatley’s philosophy was meant for a thoroughly Anglo-Saxon England, not a multicultural tyranny of knife crime, Islamist terrorism, and London Bohos addicted to Europhilia. Still, surprisingly, Wheatley’s novels, in which the bad guys are often non-English and non-white foreigners, have not yet been banned in the UK.

Wheatley should remind us that reading supernatural fiction often mines a rich conservative and identitarian vein. The American conservative Russell Kirk wrote excellent horror novels, the arch-reactionary H.P. Lovecraft created cosmic horror, and M.R. James, the literary and physical embodiment of Anglican England, was the 20th century’s finest practitioner of the classic ghost tale.

Taking back national governments must be done in conjunction with reclaiming urban spaces and the culture at large. One place where we, the English-speaking members of the National Conservative movement, can express ourselves is in scary stories.

Jake Bowyer [Email him] is the pseudonym of an American college student.

Like many of you, I’ll spend this Halloween bingeing on my favorite horror movies. Tops among them: 1968’s

Like many of you, I’ll spend this Halloween bingeing on my favorite horror movies. Tops among them: 1968’s  Richleau, a cosmopolitan of great learning who uses white magic to defeat Mocata, is something of an early hippy, or at least a believer in the slogan of “

Richleau, a cosmopolitan of great learning who uses white magic to defeat Mocata, is something of an early hippy, or at least a believer in the slogan of “ All this tracks with Wheatley’s background and personal politics. His life, wrote biographer Phil Baker in

All this tracks with Wheatley’s background and personal politics. His life, wrote biographer Phil Baker in