The cruelest month. For patriots, August was a terrible month, a month of national humiliation. I share the general anger and despair.

As if the national news wasn't depressing enough, here on Long Island we were forecast to take a major hit August 22nd from Hurricane Henri. The Derbs obediently bought in extra supplies of food and necessities. I changed the oil in my generator, topped up its gas, and gave it a test run. We were all ready for the onslaught.

It never happened. Henri changed course somehow. All we got was a couple of days of intermittent rain showers.

A nearby friend emailed in with this:

America can't even do killer hurricanes anymore.

Later in the month Hurricane Ida proved him wrong; but he caught the general spirit of the mid-August moment pretty well.

Peak crazy? Have we reached Peak Crazy yet?

- A professor of medicine at the University of California apologized to his students for saying the words "pregnant women," instead of "pregnant people," in a medical classroom.

- Tonight Show host Jimmy Fallon noted that the 2020 census result just came out this month and, quote from him: "For the first time in American history the number of white people went down." The studio audience, which was almost entirely white, erupted in cheers and wild applause.

This is totally normal and not a little bit weird at all. pic.twitter.com/E0xkk79nAA

— Paul Joseph Watson (@PrisonPlanet) August 16, 2021

- Oregon Governess Kate Brown has signed a bill ending the requirement for high school students to prove proficiency in reading, writing, and math before graduation.

- The University of Pittsburgh, in an official posting at its website, is seeking applicants for an Assistant Professorship in Structural Racism, Oppression, and Black Political Experiences.

Some follow-up notes on those.

On that first bullet point: I spotted an early instance of sex denialism five years ago, and included a link in a PowerPoint presentation I gave at AmRen that year. I thought at the time that sex denialism was so absurd it would stay out on the fringes. That was too optimistic of me. It is now orthodoxy in our medical schools. In our medical schools.

On the same topic: The Economist has this month been running a series of Biology Briefs for schools. The one in the August 21st issue included the following text:

Complex algae, animals, fungi and plants all have predictable life histories which separate out three basic aspects of development—the creation of an autonomous individual, growth and reproduction—and run them sequentially.

In some creatures, including humans, the move from one phase to the next has an obvious continuity. Fertilised eggs turn into fetuses, which become babies, who grow into two different sorts of adult, which, between them, can then produce new fertilised eggs.

Making your way in the world, August 21, 2021

"Two different sorts of adult"? Isn't that … problematic?

The Economist rarely deviates from early-2000s neocon orthodoxy. They are open-borders, race-denialist, climate-alarmist, Trump-deranged, and fully on board with missionary wars—the whole neocon deal.

That's just the line pushed by senior management, though. I bet the magazine's fully-woke junior staffers have been having angry meetings about this Biology Brief. I await the apology that must surely be forthcoming from The Economist.

And on my second bullet point, about the 2020 census numbers, David Cole had interesting things to say the other day. Sample:

Whites who checked [i.e. on the census form] "white plus something else" rose a whopping 316 percent since 2010. So while "white alone" did indeed fall to under 60 percent of the population for the first time in census history, white alone plus white combo came in at 71 percent. [Isle of L.A. Part I: The Changing Colors of the Landscapeby David Cole; Taki's Magazine, August 24th 2021.]

That, assuming Cole is right, confirms my belief that for a true picture of how the racial composition of our population is changing, you first have to get a handle on how people describe their race on census forms is changing. So far as I have seen, David Cole is the only person making a serious attempt at that.

(Cole is also an instance of something that seems quite common: the native white Californian who feels a generalized gratitude to Hispanics for having displaced blacks.)

Geezer philosophy. A friend asked me what I thought of this, from a saner time:

An individual human existence should be like a river—small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being.

—Bertrand Russell, Portraits from Memory, 1956

My thoughts? Mixed. It's a noble sentiment, elegantly expressed; but there is a great deal more to be said.

My thoughts? Mixed. It's a noble sentiment, elegantly expressed; but there is a great deal more to be said.

Whatever you think of it as a prescription for old age (Russell was 81 when he wrote it; he lived another sixteen years), it surely isn't one that many of us follow. So: pre-scriptive, OK, but de-scriptive, not much.

Look around at the geezers you know. "The river grows wider, the banks recede …"? For some, maybe. For many more, the river narrows, the banks close in, and the scope of one's interests becomes smaller and pettier, with more and more attention paid to trivial annoyances and one's own aches, pains, and malfunctions.

Speaking for myself, while I hope the scope of my interests never dwindles down to be that small, I have no desire to merge my individual being in the Cosmic All. It is the receptacle for the many pleasures I still enjoy; and it has useful work to do guiding my children in their lives and accumulating financial security for Mrs. Derbyshire in the actuarially-probable event I pre-decease her.

I care less about the great "sea" of humanity now than I did (or fancied I did) when I was twenty; but I care far, far more about these three creatures than I cared about anything at twenty.

Sure, I understand more about the world now than I did then; but where my attention is concerned, the matters I spend the most time thinking about, there's been a narrowing, not a broadening.

So I guess I'm the wrong person to bring that quotation to.

Wisdom and woo. All of that notwithstanding, I can never think unkindly of Russell. He was one of the enthusiasms of my youth.

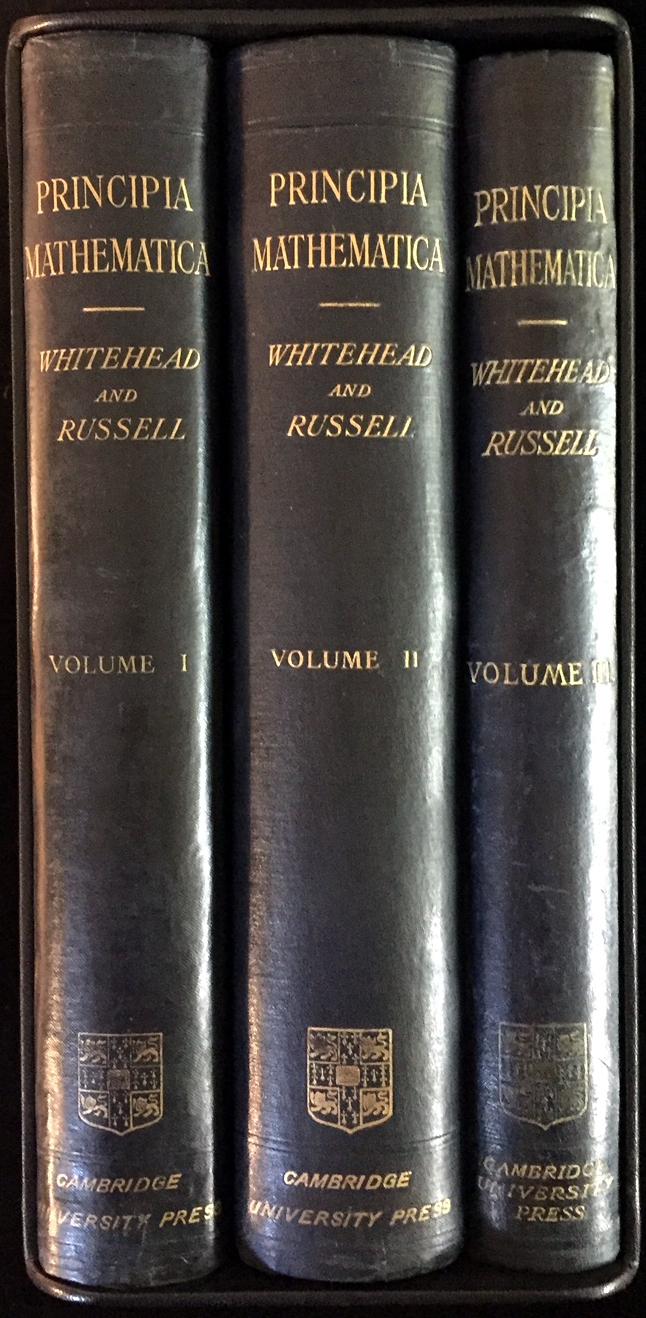

My acquaintance with him began in college with Professor Kneebone flogging us through the opening chapters of Principia Mathematica. That was hard labor, but the book's 2½-page preface got my attention for its clarity. I quoted these three sentences from it in Chapter Six of Prime Obsession:

My acquaintance with him began in college with Professor Kneebone flogging us through the opening chapters of Principia Mathematica. That was hard labor, but the book's 2½-page preface got my attention for its clarity. I quoted these three sentences from it in Chapter Six of Prime Obsession:

The very abstract simplicity of the ideas of this work defeats language. Language can represent complex ideas more easily. The proposition "a whale is big" represents language at its best, giving terse expression to a complicated fact; while the true analysis of "one is a number" leads, in language, to an intolerable prolixity.

I then added this comment of my own:

(They weren't kidding. Principia Mathematica takes 345 pages to define the number "1.")

My interest thus piqued, I read some of Russell's pop-philosophy books, including of course the History, which I still have on my shelf. When the full Autobiography came out in the late 1960s I read it with fascination. The guy was a really good—thought-provoking, entertaining—writer.

Russell was sometimes wrong, as anyone who writes sixty-odd books across seventy-odd years is bound to be. Occasionally he was silly, with a particular weakness for certain strains of early-20th-century woo, as I think that quotation at the beginning of the previous segment illustrates. I don't mean that Russell was a keen follower of Gurdjieff or Annie Besant; but woo like theirs was in the air, and he inhaled some of it.

That's perfectly normal in all eras. I've seen many cases. One of my college classmates was witty, worldly, and a very good mathematician; but I recall him waxing enthusiastic about the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who shortly afterwards became guru to the Beatles. That was late-1960s woo.

There's always something like that going around, and it appeals to a part of human nature that won't be denied.

Bugocalypse latest. Four years ago, in a Radio Derb segment and a follow-up in that month's diary, I mused on the Bugocalypse—the worldwide die-off of insect species due to habitat loss, overuse of agricultural insecticides, the introduction of alien species, and—of course!—climate change.

Speaking as a person who spends these summer months a martyr to small biting insects, I'm fine with the Bugocalypse. I do understand, though, that annihilation of the offending species would have effects cascading down through the ecosphere, with consequences far worse than a few weeks of insect bites.

Apparently I didn't know the half of it.

Apparently I didn't know the half of it.

Goulson paints a nightmarish picture of what the world might be like for his children's generation if things continue along their present path: a grim dystopia of civilisational collapse, catastrophic weather events and dire food shortages.

That's from To Bee or Not to Bee, Nigel Andrew's review of Dave Goulson's new book Silent Earth: Averting the Insect Apocalypse, in the August Literary Review.

I haven't read the actual book yet, but I shall do so as soon as the summer is over and I can put away my Deep Woods sprays, mosquito coils, and cortisone creams.

Novel of the Month. The Mrs and I rent a DVD from Netflix to watch on a Saturday night. This is more for her than for me. I'm not much of a movie person. The family joke is that we should award stars to each movie based on how long I stay awake into it.

Not that I'm totally misocinematic. I enjoy some movies; and I'll certainly agree that the big old classics — Gone With the Wind, The Godfather, The Way of the Dragon—are artistic masterpieces.

Not that I'm totally misocinematic. I enjoy some movies; and I'll certainly agree that the big old classics — Gone With the Wind, The Godfather, The Way of the Dragon—are artistic masterpieces.

If not misocinematic, however, I am definitely lethocinematic. I have no movie memory. Before I learned to hold my tongue there were regular exchanges like this:

Me: "Hey, Honey, why don't we put this movie on the Netflix rental queue?"

She, rolling eyes: "Because we saw it last year! Don't you remember anything?"

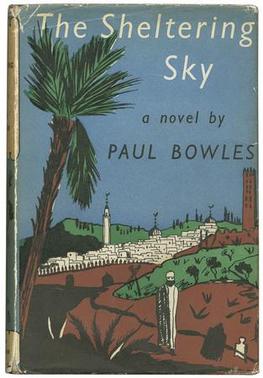

Well, the last Saturday in July our choice was The Sheltering Sky, a 1990 drama with Debra Winger and John Malkovich.

I was OK with the movie until about an hour and a half in. Then Ms. Winger was carried off solo across the Sahara, southwards from Algeria into Mali, by a bunch of natives with whom she had no language in common. That made it hard to figure out what was going on, so I gave up trying.

What movies don't do for me, books will. I find it hard to take anything seriously, even fiction, until I've seen it on printed pages. So I hiked down to the library and took out Paul Bowles' 1949 novel of the same name, from which the movie was made.

Aha! So Belqassim had three wives at their destination already, and a fourth elsewhere. The three were going to be intensely—perhaps homicidally—jealous of any new woman he brought home. That's why he wanted to pretend Debra Winger was a boy … It all sorted itself out.

Paul Bowles' novel kept my attention as a story about some slightly-eccentric New Yorkers in a very exotic place. Having seen the movie helped some, of course. However, the novel was marred for me by the impression that it carried some kind of message: something to do with Existential Anomie, the Homelessness of the Postwar Western Soul, or some such.

Paul Bowles' novel kept my attention as a story about some slightly-eccentric New Yorkers in a very exotic place. Having seen the movie helped some, of course. However, the novel was marred for me by the impression that it carried some kind of message: something to do with Existential Anomie, the Homelessness of the Postwar Western Soul, or some such.

Here and there in the text were muddy pools of metaphysical or psychological flapdoodle, sometimes in the narrator's voice (it's all third person) and sometimes spoken by one of the principals. The title comes from one of the latter instances. Chapter 13:

"You know," said Port, and his voice sounded unreal, as voices are likely to do after a long pause in an utterly silent spot, "the sky here's very strange. I often have the sensation when I look at it that it's a solid thing up there, protecting us from what's behind."

Kit shuddered slightly as she said: "From what's behind?"

"Yes."

"But what is behind?" Her voice was very small.

"Nothing, I suppose. Just darkness. Absolute night."

I'm afraid I have no patience with this kind of thing. Tennessee Williams, who did have patience for it, and who was in fact a successful retailer of it, tells us this:

In its interior aspect, The Sheltering Sky is an allegory of the spiritual adventure of the fully conscious person into modern experience …

I suspect that a good many people will read this book and be enthralled by it without once suspecting that it contains a mirror of what is most terrifying and cryptic within the Sahara of moral nihilism, into which the race of man now seems to be wandering blindly. [An Allegory of Man and His Sahara by Tennessee Williams; The New York Times, December 4th 1949.]

Sure, whatever, Tenn. Novel-wise, I'm with Sam Goldwyn: Messages are for Western Union. (Nowadays I guess for texting.) Just tell me a story.

Bomu, Bozo, and Bobo. The Sheltering Sky left me with a slight mystery. The text is lightly sprinkled with bits of French and what I supposed to be Arabic. On page 283 of the 2014 Ecco paperback edition, for example (Chapter 27) we get:

As Belqassim fed her a cake, she sobbed and choked, showering crumbs onto his face. "G igherdh ish'ed our illi," sang the musicians below, over and over, while the rhythm of the hand drum changed, slowly closing in upon itself to form a circle from which she could not escape.

OK, but what do the italicized words mean? I have a neighbor whose first language was Arabic; I asked him. He did not know. Huh. One of the languages of Mali, perhaps? What are the languages of Mali? I asked Wikipedia.

OK, but what do the italicized words mean? I have a neighbor whose first language was Arabic; I asked him. He did not know. Huh. One of the languages of Mali, perhaps? What are the languages of Mali? I asked Wikipedia.

Mali has 12 national languages beside French and Bambara, namely Bomu, Tieyaxo Bozo, Toro So Dogon, Maasina Fulfulde, Hassaniya Arabic, Mamara Senoufo, Kita Maninkakan, Soninke, Koyraboro Senni, Syenara Senoufo, Tamasheq and Xaasongaxango.

And that's just official national languages. Wikipedia tells us that in there among speakers of Bomu and Bozo, 1.89 percent of Malians speak Bobo.

Why is Bobo denied the official status granted to Bomu and Bozo? Looks to me like a nasty case of anti-Bobo discrimination—Bobophobia.

The furthest shores of bookishness. Writing about Bertrand Russell back there, I fell to browsing in  the Autobiography. Bookish I may be, but Russell had a friend even more bookish than me: the poet Robert Trevelyan. This is September 1914.

the Autobiography. Bookish I may be, but Russell had a friend even more bookish than me: the poet Robert Trevelyan. This is September 1914.

Bob Trevelyan was, I think, the most bookish person that I have ever known. What is in books appeared to him interesting, whereas what is only real life was negligible. Like all the family, he had a minute knowledge of the strategy and tactics concerned in all the great battles of the world, so far as these appear in reputable books of history. But I was staying with him during the crisis of the battle of the Marne, and as it was Sunday we could only get a newspaper by walking two miles. He did not think the battle sufficiently interesting to be worth it, because battles in mere newspapers are vulgar. [The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, Vol. 1, Chapter 3.]

A good cigar is a smoke. A late weekday evening in mid-August. Mrs Derb is out with friends. My next-door neighbor has come over. He and I both like to smoke an occasional cigar.

So we are sitting out on the deck at back of my house, smoking our cigars, drinking (he, beer; me, wine), and exchanging opinions, experiences, stories, and jokes.

We are facing south, looking down the length of my modest suburban back lawn to the bushes at the bottom and the big old oak tree at the property line. Beyond the range of the deck light the lawn is dark. The oak tree is perfectly dark, a huge black shape against the less-dark sky. The phrase "the dark-boughed tree" comes to me from somewhere, but I can't place it and neither can my neighbor.

My cigar is a Romeo y Julieta. I don't know squat about cigars; but on the rare occasions my Dad smoked one, that's what he smoked, so I follow suit from filial piety. My neighbor's is a New World. I tell him the old Clarence Darrow story, which he did not know.

My cigar is a Romeo y Julieta. I don't know squat about cigars; but on the rare occasions my Dad smoked one, that's what he smoked, so I follow suit from filial piety. My neighbor's is a New World. I tell him the old Clarence Darrow story, which he did not know.

During an opponent's closing argument, Clarence Darrow would run a paper clip through his cigar, letting an enormous ash build, mesmerizing the jurors and, of course, diverting their attention.

Apart from our voices and the rasp of crickets, all is silent. We live in the bosky outer-outer suburbs of a great city—in the countryside, as good as: there's a working farm just a mile away. No significant traffic passes within earshot late evenings.

Our voices in the silence, my deck light in the darkness. The air is warm. Cigar smoke curls up towards the dark-boughed tree. My puppy snuffles about on the lawn, following the scent of some long-departed squirrel. Life is good.

Back in the house, in my study, I go online to look up that phrase. Walter de la Mare, right. How easy everything is nowadays!

Happy is the man, not who has no car, but who has no need of a car, or needs one only very occasionally and then takes a taxi. [Auto Focus by Theodore Dalrymple; Taki's Magazine, August 27th 2021.]

Setting aside the main point of Dalymple's article—it's mostly a grumble about electric cars—I can confirm that carlessness is a happy state. I have had no car for three or four years now, and find it a great simplification and, yes, an increase in personal happiness.

I'll allow that I'm a special case, with no real need for a car. I work from home, so I don't need a car for commuting. I live in a small, compact town, fifteen minutes walk from anywhere I need to go: drugstore, hardware store, library, post office, … Walking is healthful and I enjoy it.

My wife works from home, too. She has a car, which I can borrow for an hour or so well-nigh any time I want to. You may say that makes my claim to carlessness a bit of a cheat, and you may be right. I don't care. I don't have a car: that's one less thing to worry about and pay for. Sure, having your own car gives you freedom of a kind. Not having a car gives you freedom of another kind—a kind I prefer.

The two or three times a year I need to go on a long trip—to a conference, for example—I rent a car. The cost, annualized, is way cheaper than owning a car full-time. And rental has the advantage that you get to try out the latest models with all their cute gadgets.

In an emergency, there are still taxis. People tell me that won't be the case for much longer, as ride-hire services like Uber are putting all the taxi firms out of business. That could be a problem, as I don't have a smartphone …

Modernity, you can't escape it.

Pedestrianism. Having unmasked myself there as a dogged pedestrian, I cannot forbear noting this story from the Beeb about a weird sports fad in post-Civil War America.

Pedestrianism was a sport of epic rivalries, eyewatering salaries, feverish nationalism, eccentric personalities and six-day, 450-mile walks …

The rules were simple—essentially, contestants were required to walk in circles for six days in a row, until they had completed laps equivalent to at least 450 miles (724km). They could run, amble, stagger or crawl, but they must not leave the oval-shaped sawdust track until the race was over. Instead they ate, drank and napped (and presumably, performed other bodily functions) in little tents at the side, some of which were elaborately furnished. [The strange 19th-Century sport that was cooler than football; BBC Future, July 28th 2021.]

(Four years ago Matthew Algeo published a book about pedestrianism, which I somehow missed.)

How strange the world is!—and the human world is strangest of all.

A hundred years ago. Under the influence of Mark Steyn's Hundred Years Ago Show, I have been browsing in some of the relevant political literature.

To be precise, I've been reading up on Warren Harding, who was our president a hundred years ago. This month I've read Robert Ferrell's The Strange Deaths of President Harding, John Dean's Warren G. Harding, and Robert Murray's The Harding Era; Warren G. Harding and His Administration, which knowledgable friends told me is definitive.

To be precise, I've been reading up on Warren Harding, who was our president a hundred years ago. This month I've read Robert Ferrell's The Strange Deaths of President Harding, John Dean's Warren G. Harding, and Robert Murray's The Harding Era; Warren G. Harding and His Administration, which knowledgable friends told me is definitive.

I knew, from scattered random readings at the time of my Calvin Coolidge fixation back in the 1990s, that the popular image of Harding is a gross misrepresentation. These authors fill in the details.

Harding was not a slob, as Alice Roosevelt Longworth asserted. His speeches were not word salad, as H.L. Mencken sneered. He was more trusting of old friends than he should have been, but not personally corrupt. His presidency was a modest success.

All the aforementioned books were skeptical of Nan Britton's claim to have been Harding's mistress and to have borne his child; although John Dean's book, which came out in 2004, suggested that DNA testing could be done to settle the matter. It eventually was done: yes, Harding was the baby daddy. Whether Ms Britton's more lurid claims were also true—the claim, for example, that he banged her in a White House storage closet—will never be known for sure.

Harding our worst president? Murray:

He was certainly the equal of a Franklin Pierce, an Andrew Johnson, a Benjamin Harrison, or even a Calvin Coolidge. In concrete accomplishments, his administration was superior to a sizable portion of those in the nation's history. Indeed, in establishing the political philosophy and program for an entire decade, his 882 days in office were more significant than all but a few similar short periods in the nation's experience.

Murray's book was published in 1969, before Jimmy Carter's presidency and, of course, before Joe Biden's.

The memorial eulogy for Harding was given to a joint session of Congress on February 28th, 1924 by Harding's Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes, a man of the highest ability and integrity. (He was Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1930 to 1941.) The eulogy was fulsome in praise of the dead president.

"In lapidary inscriptions a man is not upon oath," and the same applies to memorial addresses; but there is no reason to think Hughes spoke other than with complete sincerity. He was known to have had great personal liking and respect for Harding.

Hughes closed his address with some lines the poet James Russell Lowell had written in an 1889 letter to Josiah Quincy in praise of Grover Cleveland, who Lowell and Quincy both supported. Cleveland had lost the White House the year before; he regained it in 1892.

Let who has felt compute the strain

Of struggle with abuses strong,

The doubtful course, the helpless pain

Of seeing best intents go wrong.

We, who look on with critic eyes,

Exempt from action's crucial test,

Human ourselves, at least are wise

In honoring one who did his best.

Movie of the Month. I was going to slip right out of August without a Movie of the Month. Then, for the last Saturday night, our Netflix rental was Georgetown, Christoph Waltz's 2019 dramatization of the Albrecht Muth affair, which ended abruptly for Mrs. Muth in August 2011.

Having no interest in Washington, D.C. high society, I had never heard of Muth and his audacious scam. Watching the movie, I had trouble believing that it was, as advertised, based on a true story.

Having no interest in Washington, D.C. high society, I had never heard of Muth and his audacious scam. Watching the movie, I had trouble believing that it was, as advertised, based on a true story.

Did Muth really, for example, name his outfit the Eminent Persons Group? Wasn't that a tell? Who but a con artist on the make would think up a name like that? (In the movie it's his wife's suggestion.)

But yes, it's all true, it all happened. At any rate, the movie follows closely Franklin Foer's July 2012 story in The New York Times, The Worst Marriage in Georgetown. If you think that Washington, D.C. movers and shakers are the smartest people on the planet, brace yourself for disillusion before following that link.

Franklin Foer's story is well and professionally done; but, as several Times readers complained, it ends—like Mrs Muth—too abruptly, as if the last couple of paragraphs had just been lopped off. Any veteran freelancer knows, and could tell those readers, that this style of newspaper and magazine editing is much more common than you'd think. In fact I have a very fascinating story about this.

John Derbyshire [

John Derbyshire [