Earlier by Anthony Boehm: June 17, 1953: Sixty Years of “Electing A New People”

The first reports are typical—“terrorism suspected.” Our elites never tire of “suspecting” a clear case of terrorism is just that—the “Strassburg-born” perp, after all, shouted “Allahu akbar” during the whole event. The whole murderous event. [France Declares Strasbourg Shooting to Be an Act of Terrorism, by Elian Peltier and Aurelien Breeden, NYT, December 12, 2018] But how did he, identified as a French citizen “with North African roots ”as RT puts it, named Cheriff Chekatt in a region where typical native names are Schwarz, Klein, Moschenross, become a “Strasbourg man” or as you can see below, a “local”?

In fact, his presence in the Alsatian capital is easily explained—replacement of a people.

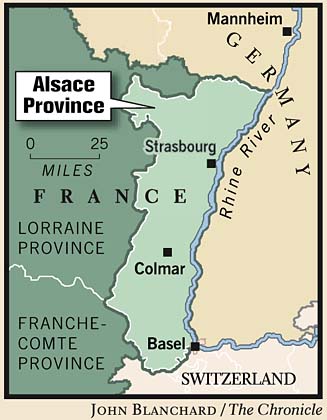

![]() A short excursion into the history of Strassburg (the spelling I prefer) and Alsace explains how Chekatt came to be born there. France was able slowly to conquer the southwest German region in the 1600s, aiming for a natural frontier on the Rhine river. But once the conquest was complete, the French monarchy was willing to leave the Alsatians (Elsaesser in High German and the local dialect) in peace. Few attempts were made to force the locals to speak or even feel French. As long as they paid their taxes and were loyal subjects of the French king, they were left alone. The Alsatians were recognized by the government as a “foreign body” in the French nation but tolerated since they were not considered malignant (unlike the Huguenots) and their German motherland was divided and unable to liberate them.

A short excursion into the history of Strassburg (the spelling I prefer) and Alsace explains how Chekatt came to be born there. France was able slowly to conquer the southwest German region in the 1600s, aiming for a natural frontier on the Rhine river. But once the conquest was complete, the French monarchy was willing to leave the Alsatians (Elsaesser in High German and the local dialect) in peace. Few attempts were made to force the locals to speak or even feel French. As long as they paid their taxes and were loyal subjects of the French king, they were left alone. The Alsatians were recognized by the government as a “foreign body” in the French nation but tolerated since they were not considered malignant (unlike the Huguenots) and their German motherland was divided and unable to liberate them.

The French Revolution and Napoleonic era changed that.

The Revolution brought democracy, which the Alsatians loved, but it also brought centralization and forced assimilation, which they hated. When the French monarchy was restored in 1815, the centralism remained but the democracy went out the door. Alsatians left the region in large numbers, heading to German settlements in Russia, the Banat region of Austria-Hungary and to the US, where they formed part of the ethnicity now referred to as the Pennsylvania Dutch, heavily impacting the PA Dutch German dialect. They also made a compact settlement in Castroville, Texas, where the older generation still speaks the dialect today.

In Alsace, assimilation to France occurred in the elite and upper middle class, which took to speaking French (at least in public) and aping French culture. But the workers and farmers continued to hold on stubbornly to their German language and local identity. The population remained well over 90% German-speaking.

In 1871, France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian war and Alsace and the German-speaking part of Lorraine were liberated from the French yoke. [VDARE.com Note: We’re aware that history written by a Frenchman would have substantially different tone.] While the elite and middle class with their ties to France and control of the media, claimed that the transfer was unwanted, the lower classes welcomed the ability to send their children to schools in their native language and the churches welcomed the rights they obtained under German law—the secular French state gave them little support. This was the point at which ten-year-old Alfred Dreyfus’ prosperous Jewish family chose to leave for France—where, ironically, he was subsequently the protagonist in the notorious Dreyfus Affair spy scandal.

For the next two generations Alsace prospered under German rule, obtained special rights, despite occasional tensions (the 1913 Zabern incident for one.). By the outbreak of World War I, there was no longer a question as to the loyalty of the Alsatians to Germany. They served loyally in the Imperial forces and even American-born Alsatian-Americans (one known personally to the author, Fritz Waag) returned to Europe to, in his words, “keep Alsace part of the Fatherland.”

With the German collapse in 1918, the Alsatians declared themselves an independent Leftist state, which ceased to exist when the French army marched in. The occupation forces were amazed to find that almost no one spoke French.

Paris immediately instituted a policy of forced assimilation, expelling some 150-200,000 persons considered German irreconcilables from Alsace. [See The Expelled Germans Of Alsace-Lorraine After Versailles, Institute for Research of Expelled Germans.] This led to the growth of a strong autonomy movement. The Alsace-Lorraine “Heimatbund” was created in 1926 to defend the German language in the region. But many of its leaders and leaders of autonomist political parties were subjected to prosecution for secessionism and jailed.

When the Nazi Germany conquered the region in 1939, it did not formally annex it, but treated it as a part of Greater Germany. Alsatians were subjected to forced military service. When France retook the region in 1944, an even harsher assimilation policy was instituted and the back of the autonomist movement was broken. Many of those who had served in the German army were forced to join the French Foreign Legion to prove their loyalty to France.

Strassburg’s and Alsace’s Christmas Markets have been doing business since before the Reformation and were originally all “Weihnachtsmaerkte” of the sort that can still be seen in Bern, Berlin, Munich, Vienna or any other German-speaking city. The top French Christmas Markets are all in Alsace—in French-speaking areas there is no tradition of Christmas Markets. As in the U.S., the Christmas Market is a German tradition.

As one tourism site states

Let’s start the season of Advent with a list of our 10 most beautiful Christmas markets in France’s North-East, all situated in the Alsace, Franche-Comté and Lorraine regions. Christmas markets are called “Marchés de Noël” in French and are organised in the historic town or village centre. Although they are a traditional event in Alsace, many of these French Christmas markets have been “exported” to other parts of the country, from Lille to Rouen and Bordeaux.

So Alsatian Christmas Markets are tolerated—but the language and culture that gave rise to them have been under constant attack since 1918. Some have resisted and continue to resist. [Alsace fights back: a French David vs. Goliath story , by Lucas Goetz, OpenDemocracy, December 7, 2014]

A major part of Paris’s assimilation program was to encourage the employment of cheap North-African labor in the heavy industries in Alsace and Lorraine. These migrants spoke only rudimentary French, but no German at all, so their presence increased the speed of the “normalization”—assimilation—of Alsace into a centralized French state.

A similar phenomenon has been noted in Quebec, where most foreign immigrants speak English and help to break down the Francophone majority.

In other words, the victims of the Strassburg Christmas Market massacre owe Mr. Chekatt’s presence in their city in no small part to France’s intolerance of its autochthone ethnic minorities.

The Strassburg murderer was thus neither a real Strassburger, nor an Alsatian nor even a Frenchman. He was an uprooted North African, probably in his mind attempting to revenge the perceived wrongs done to his people, his religion and his family by the French.

The irony is that one of his victims was a Thai tourist and another an Italian journalist. But all of Alsace and in particular, Strassburg are victims too.

Symbolically, the city has essentially been closed down by the attack—and its major newspaper has not been able to appear, since workers can’t get to the newspaper offices.

Another example of what happens when the elites determine to elect a new people—and to destroy a national culture.

Anthony Boehm [Email him] is a federal civil servant.

A short excursion into the history of Strassburg (the spelling I prefer) and Alsace explains how Chekatt came to be born there. France was able slowly to conquer the southwest German region in the 1600s, aiming for a

A short excursion into the history of Strassburg (the spelling I prefer) and Alsace explains how Chekatt came to be born there. France was able slowly to conquer the southwest German region in the 1600s, aiming for a