Here’s a very interesting new paper that takes Cavalli-Sforza’s old techniques for measuring genetic distance of one population (racial group) from another and applies them to measuring how far apart different countries are in culture and psychology, using Americans and Chinese as well-studied benchmarks.

Beyond WEIRD Psychology: Measuring and Mapping Scales of Cultural and Psychological Distance

Michael Muthukrishna, Adrian V. Bell, Joseph Henrich, Cameron M. Curtin, Alexander Gedranovich, Jason McInerney, Braden Thue

Decades of psychological research designed to uncover truths about human psychology may have instead uncovered truths about a thin slice of our species – those who live in Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic (WEIRD) nations (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Researchers often assess the generalizability of these findings by comparing Western nations to East Asian nations, but are increasingly documenting differences in small-scale societies. Nonetheless, there exists no systematic method for determining which societies will provide useful comparisons or even the size of the psychological differences—the cultural distance—between societies, be they non-Western, less-educated, less-industrialized, poorer, non-democratic or some subset of these. And even within WEIRD nations, there are psychologically-relevant cultural differences (Henrich et al., 2010; Lee et al., 1995; McCrae, Terracciano, & 79 Members of the Personality Profiles of Cultures Project, 2005). These quantifiable differences are also apparent to tourists, who can tell you about laid-back Aussies, precise Swiss, or friendly Canadians. Our species is also fundamentally cultural, and thus these cultural differences are also psychological differences: from norms and attitudes, to the degree to which these norms are enforced, to low-level perception of color and visual illusions (Henrich, 2016).

For example, compared to Americans (the horizontal axis below), Canadians are closest in personality and cultural emphases and Egyptians are most distant, about an order of magnitude more un-American than are Canadians. Compared to Chinese (vertical axis), Vietnamese are closest and Qataris are most distant.

![Screenshot 2018-11-27 15.20.04]()

Yemenis up in their isolated high altitude land are the most exotic from both America and China overall. (Which is one reason I’m sore about the Saudis dropping bombs on Yemen — it’s a really different place, a semi-urban North Sentinel Island of culture.)

These are not prima facie absurd results. They suggest, for example, that Islam forms a sort of third pole to America and China.

Sub-Saharan Africa is not well-studied, so it might someday form a fourth pole when more questions are asked relevant to its distinctiveness. At present, for example, on the chart above, Zambia comes out in the middle of the pack. But that might have less to do with Zambia being a ho-hum, run of the mill culture than that the academics in America and China who have run the most studies were not in touch with what makes sub-Saharan cultures distinctive.

And perhaps the Pacific and Amerindian tribes might emerge as additional poles. Frequent traveler Tyler Cowen, for example, recently suggested that the Bolivian highlands remain more culturally distinctive than even Yemen.

Or who knows what else is out there to be discovered?

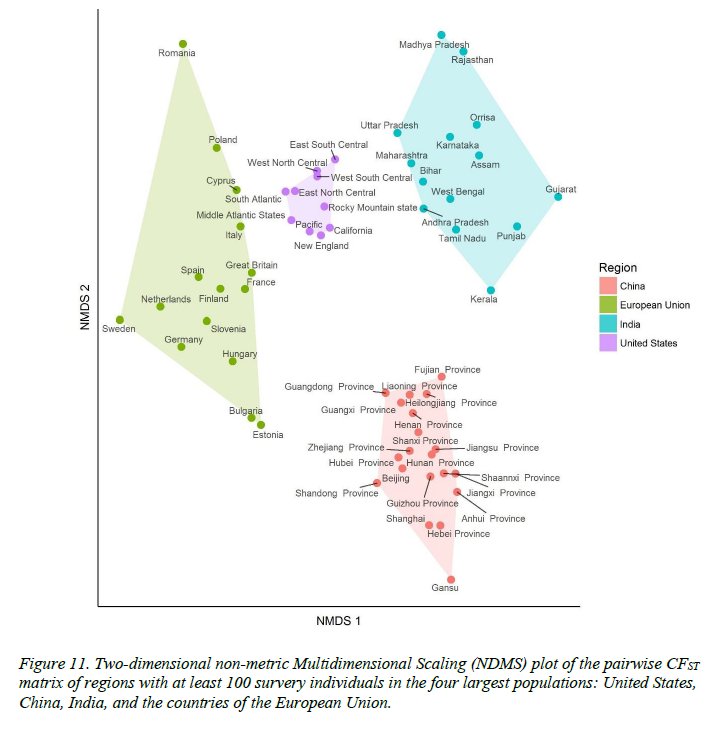

They can also measure cultural difference among regions within a country or within the EU. America is much more geographically homogeneous than is the EU, India, or China:

![]()

Another question this methodology could consider would be to look across time as well as space. For example, how fast is Chinese immigration into Australia moving Australia from being very similar to America to becoming more like China?

As the Flynn Effect showed, tests that were devised to work across space sometimes give unexpected results across time.

[Comment at Unz.com]