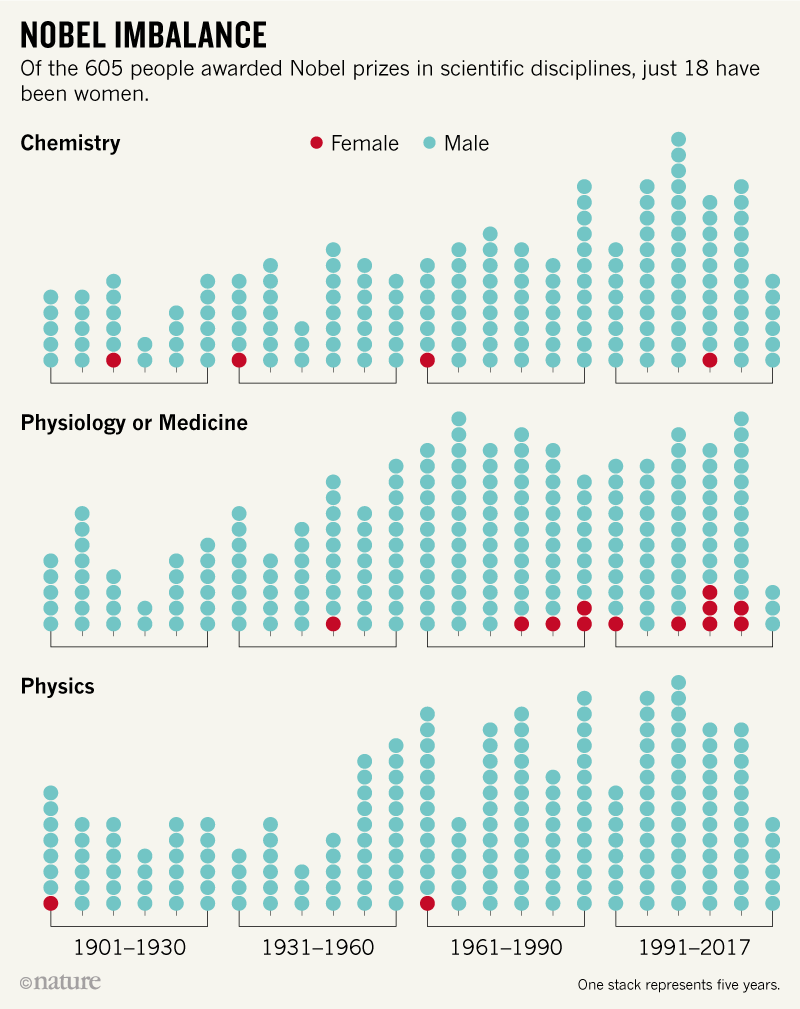

As I’ve been noting since 2005, the three hard science Nobel Prizes have long been resistant to the Demand for Diversity because, well, they are the immensely prestigious Nobel Prizes and so they don’t have to play that way. But all good things must come to an end. From Nature:

What the Nobels are — and aren’t — doing to encourage diversity

The prize-awarding academies are making changes to their secretive nomination processes to tackle bias, but some say the measures don’t go far enough.

Elizabeth Gibney

September 28, 2018If a woman wins the Nobel Prize in Physics next week, she will be the first to do so in more than 50 years. Over the same period, just one woman has won in chemistry.

You might almost think that women prefer the Life Sciences (i.e., the Physiology or Medicine Nobel Prize). I had my life saved from dying of cancer back in the 1990s by, in part, a brand new breakthrough drug. I presume that a lot of women worked on developing that drug. So I say to the many women working in the Life Sciences: Thanks!

On the other hand, not that many women are really into the Death Sciences.

The concept of the Death Sciences (physics foremost) was indelibly defined by physicist Robert Oppenheimer when discussing his thoughts about being the lead inventor of the atomic bomb: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Not too many girls have been galvanized by that quote, but more than few boys, trust me, have thought Oppenheimer’s quote was the coolest thing anybody ever.

This gender imbalance is the subject of increasing criticism, much of which is aimed at the Nobel committees that award the honours. In the awards’ history, women have won only 3% of the science prizes (see ‘Nobel imbalance’), and the overwhelming majority have gone to scientists in Western nations. Some argue simply that the prizes tend to recognize work from an era when the representation of women and non-Western researchers in science was even lower than it is today. But studies repeatedly show that systemic biases remain in the sciences, and the slow pace of progress was especially evident in 2017, when there were no female laureates for the second year in a row….

The organizations that award the science prizes have now begun tweaking their nomination processes to encourage gender and geographic diversity among prize nominees and, they hope, winners. But it’s unclear how soon the effects of these efforts will be felt.

… For the first time, the committee will explicitly call on nominators to consider diversity in gender, geography and topic for the 2019 prizes.

The request will be included in invitation letters scheduled to go out by early October to the thousands of scientists asked to nominate candidates for each prize. “We don’t work in a vacuum. We need the scientific community to see the women scientists, and to nominate those who have made outstanding contributions,” Hansson told Nature. …

Another tweak is also in the works. For the first time, the letters for physics and chemistry prizes will emphasize that nominators can put forward names corresponding to three different discoveries, something that, although already possible, was not highlighted until now meaning it might have been underused. (Nominators were also already allowed to put forward multiple names for a single discovery.)

This approach might lead to greater diversity, because research shows that people make more varied choices when selecting multiple candidates than when they pick just one, says Iris Bohnet, a behavioural economist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “I’m delighted to hear about the change,” she says.

And around two years ago, the committees overseen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences began to deliberately increase the number of women who are eligible to make nominations.

The prize in physiology and medicine already has a better record: women make up 21% of the past decade’s laureates.

You might almost imagine that women tend to be more interested in physiology and medicine than in physics, but that can’t be true because that’s a stereotype. As Science teaches us, stereotypes can’t be true.

But the Nobel Assembly remains concerned about gender imbalance, says its secretary-general, Thomas Perlmann. The assembly is increasing the number of women and junior scientists that it invites to nominate, and is continually looking at how it formulates its invitation letter, he says.

Rice says that boosting women among nominators — and in the prize-giving bodies themselves, which both organizations have also done — is positive, but unlikely to have much impact because many studies show that, raised with the same cultural biases, both genders tend to favour men. Perlmann, however, says that the assembly has noted that women do have a slightly higher probability of nominating other women.

Dammit, women scientists, stop being so objective and become more sexist like we want you to be!

Bohnet and Rice proposed further steps that the academies could take during a February conference on gender convened by the Nobel committees and the Nobel Foundation board. …

More radically, they could also insist that their shortlists have equal numbers of men and women, suggests Rice. Or the awarding bodies could, for a single year, decide to give all the prizes to women. Rice notes that this has happened in reverse dozens of times.

Uh, no, that has not happened in reverse. One sex was never excluded, not even 115 years ago, when Madame Curie shared in the 1903 Nobel in physics, and then was the sole winner of the 1911 Chemistry Nobel.

“There are few things that could shake up the scientific world as much as that, in terms of forcing people to consider the scientific contributions of women,” Rice says. “Needless to say, that particular proposal didn’t fly.”

Rice notes that gender-equality measures can meet resistance because some people worry that they risk reducing quality. But “the idea that there aren’t high-enough quality women in those fields is ridiculous”, he says.

Science!

… Rice says that if the Nobel prizes don’t start better acknowledging the work of women, their reputation will suffer. Other prizes also need to take action, he notes. In mathematics, the Fields Medal was awarded to a woman for the first time in 2014, and the Abel Prize has never been awarded to a woman. “So the whole prize thing has serious problems,” he says.

In as-yet unpublished work, Brian Uzzi, a social scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues analysed several scientific prizes and found that in some fields, women have been winning prizes at a rate on a par with their representation. However, those prizes were more likely to be of lower ‘status’ and cash value, and were often related to teaching, rather than research.

That might be down to stereotypes about women and men, Uzzi says. “The way to break stereotypes is with role models.”

One Weird Trick to Change the Human Race! If only Madame Curie were more famous …

The secret is to have more women winners.”

It’s almost as if women like to behave in stereotypical fashion. But that would be anti-Science!