Until we stand, all will fall.

Robert E. Lee.

Stonewall Jackson.

George Washington.

Thomas Jefferson.

Teddy Roosevelt.

All the monuments will come down to the aforementioned men, and other white men such as Christopher Columbus, Francis Scott Key, Henry Clay, and... any white man who never prostrated himself for the advancement of nonwhites.

![]()

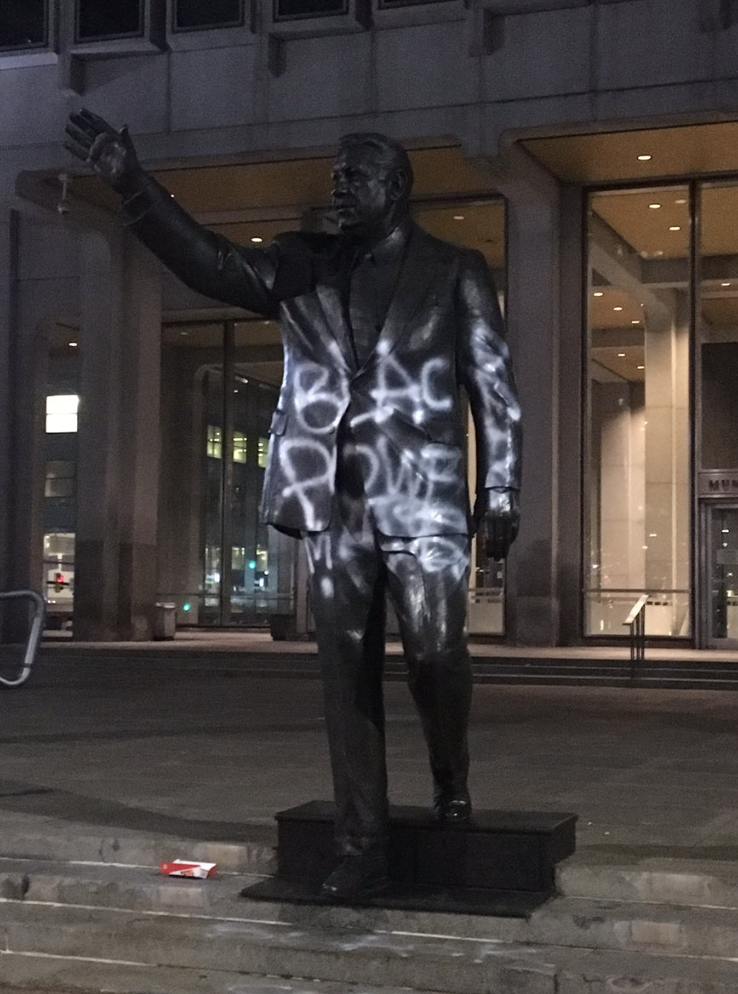

Because of the complaints of a radical SJW Asian Councilwoman, the statue to Frank Rizzo in Philadelphia (vandalized in the picture with "black power" written on it) will come down

Next on the chopping block?

After Vandalism, Controversy, Philly to Move Frank Rizzo Statue, NBC Philadelphia, November 4, 2017After months of controversy and several protests, the city announced that the Frank Rizzo statue will be moved from its current location across from Philadelphia’s City Hall.

City officials made the unexpected announcement Friday that the decision was reached after thousands of individual recommendations from the public and careful consideration.

There was no exact date for the 10-foot monument's removal from its perch on Thomas Paine Plaza in front of the Municipal Services Building. The full-body, hand-waving Rizzo looks south, several yards from the busy intersection of JFK Boulevard and North 15th Street.

City Managing Director Michael DiBerardinis said in a statement that "potential new locations" have been identified, but he did not name them.

“Earlier this year we initiated a call for ideas on the future of the Rizzo statue,” DiBerardinis said. “We carefully reviewed and considered everyone’s viewpoints and we have come to the decision that the Rizzo statue will be moved to a different location. This decision comes at a time when we have begun the preliminary stages of planning to re-envision Paine Plaza as a new type of inviting and engaging public space.”Rizzo served as mayor from 1972 to 1980. His controversial legacy stretches further back to his rise through the ranks of the police department to eventually become commissioner.

He became the ire of local activists and protesters amid the national debate about statues honoring leaders of the South during the Civil War, particularly monuments displayed prominently on public property in southern cities.

Councilwoman Helen Gym first stirred the anti-Rizzo statue fervor when she tweeted in August that it should be removed.

Over the summer, the statue was vandalized at least twice. The statue was egged and a man was arrested for spray-painting "black power" on it.

After asking the public to weigh in on if the statue should be moved, almost 4,000 proposals were received.

Rizzo was a hero, a beacon of hope for western civilization in one of America's great cities,

long burdened with a black crime problem even W.E.B Du Bois lamented.

In Joseph R. Daughen and Peter Binzen’s biography of Frank Rizzo–a man the police of Philadelphia referred to as “the General”–we learn the reality of black crime never changes (and a great reason why present-day SJWs hate his memory).

Outside of the crimes of passion you see in the white community or mass violence committed by antisocial freaks (the occasional white psychopath), the frighteningly repetitive frequency of individual black criminality - aggregated together - equals the death of a city’s viability.

The good people leave when the bad are allowed to flourish.

And as The Cop Who Would Be King makes clear, Rizzo stood for the good people:

The city did not erupt, as Detroit, with more than forty dead, and Newark, with 25 dead, did. And for that, Philadelphians, black and white, were grateful. But the blacks would not remain so grateful after Rizzo’s style as commissioner became better known to them, after they had seen him action on other occasions.![]() These occasions would reinforce an uneasy suspicion that Rizzo was at heart a racist, a northern Bull Connor whose concept of justice consisted of the speedy and expert truncheoning of the skulls of blacks. Rizzo would protest against this description of himself, but his unrestrained, implicitly violent public comments only served to strengthen that impression. Indeed, an examination of his record tended to support Rizzo. His truncheon was used with the same abandon on whites that it was on blacks.

These occasions would reinforce an uneasy suspicion that Rizzo was at heart a racist, a northern Bull Connor whose concept of justice consisted of the speedy and expert truncheoning of the skulls of blacks. Rizzo would protest against this description of himself, but his unrestrained, implicitly violent public comments only served to strengthen that impression. Indeed, an examination of his record tended to support Rizzo. His truncheon was used with the same abandon on whites that it was on blacks.

But far more blacks than whites had contact with the police. Four out of five persons arrested for major crimes in Philadelphia were black. Blacks were responsible for most of the street crime, most of the murders, most of the rapes, most of the robberies. It was random violence by blacks against whites–a college student stabbed to death as he waited for a subway train, a 17 year old youth murdered (because he refused a black gang’s demand for money) as he entered a downtown bank three blocks from City Hall at high noon–that terrorized many whites and made them afraid to walk the streets.

And when acts of violence occurred, Rizzo responded in characteristic fashion, either with inflammatory rhetoric, which blacks believed was directed at them as a racial minority, or with strong, personal action, which was considered incontrovertible evidence of a sadistic hatred of blacks.

Rizzo’s incendiary reaction to crimes of violence led to similar, if less intense, perceptions of him by the frightened whites. When he denounced a particularly atrocious crime committed by a black, these whites saw him as a sympathetic ally who was determined to keep the blacks in line. But when he condemned an act by a white criminal–as he did whenever one took place–both blacks and whites were able to accept that condemnation for what it was: an attack on a specific individual for a specific offense.

The perception of Rizzo as a racist, while related to his own words and actions, undoubtedly was partially rooted in the way people thought about themselves.

Blacks historically had been discriminated against as a group, because they were part of a group that was locked out. A door slammed shut in the face of one black was a door slammed on all blacks. When Rizzo ranted about a specific black criminal, there was a tendency to interpret this as a general assault on the entire race, an assigning of guilt to blacks as a group.

Whites, who were used to being treated as individuals, did not feel threatened when Rizzo attacked a white criminal. But a good number of these same whites still saw blacks as a group, rather than as a collection of individuals. And, when Rizzo reacted against a black criminal, they perceived it as a rebuke to the group, as well as to the individual. The vocal support Rizzo received from whites who lumped all blacks together, the whites who lived in the neighborhoods where resentment against the blacks was the highest, heightened black suspicion of him.

As police commissioner, Rizzo did nothing to help his cause among blacks. In his public statements, he seemed unable to distinguish between black criminals and black activists who challenged authority on the basis of real grievances. In this, he was not unlike those whites who watched with mounting fury the television accounts of blacks marching in protest, occupying public buildings. Demonstrators were seen as thugs. There were “good” blacks, who obeyed the law and sat behind locked doors in their crime-ridden neighborhoods, and there were “bad” blacks, who stabbed and pillaged and defied authority, or encouraged others to do so.

“Hoodlums have no license to burn and sack Philadelphia in the name of civil liberties and civil rights activities,” Rizzo said…(p. 131-132)

Until we stand, all will fall.