Moynihan had sent Nixon Richard Herrnstein’s September 1971 Atlantic article “I.Q.”[PDF, 18 pp.]. Nixon told Moynihan: "Nobody on my staff even knows I read the goddamn thing," to which Moynihan replies "Good!"

Nixon went on, regarding ”this Herrnstein stuff”:

Nixon: “Nobody must know we’re thinking about it, and if we do find out it’s correct, we must never tell anybody.”What both Herrnstein and Jensen were saying—and being pilloried for—was that you can’t close an IQ gap that’s hereditary by Head Start and free school breakfasts. Jensen’s famous 1969 Harvard Educational Review article was called How Much Can We Boost IQ and Scholastic Achievement? [PDF]Moynihan: “I’m afraid that’s the case.”

Nixon: “I’ve reluctantly concluded, based at least on the evidence presently before me –and I don’t base it on any scientific evidence—that what Herrnstein says, and what was said earlier by [Arthur] Jensen, and so forth, is very close to the truth.”[MP3]

The answer, then and since is “Not much.”

In the course of this conversation, Nixon also reveals that he’s read the September 1971 Commentary article “The Limits Of Social Policy” by Nathan Glazer—all of which made him better informed about the intellectual arguments about race, IQ, and welfare than almost all subsequent Presidents.

At the point where the YouTube clip picks up below, Nixon is talking about the fact that Democrat Edmund Muskie had told reporter Frank Reynolds in a TV interview that a ticket with a black Vice-President would lose in 1972.

Nixon had piously criticized him for saying that. But in this clip, Nixon says that, even if private polls showed that a black (or a Catholic or a Jew) would have negative effects on the ticket, no one is supposed to say that.

Now, I remember the Muskie/Nixon controversy, because William F. Buckley wrote a column about it:

Concerning Senator Muskie's observation, for which Senator McGovern has given him hell— that there would be little point in putting a black Vice President on his ticket, inasmuch as both of them would proceed to lose— a few observations.You can hear Nixon defending disingenuousness above—because Nixon famously had his conversations taped.Senator Muskie's Gaffe, September 28, 1971.

- President Nixon's retort that Senator Muskie had "libeled " the American people is both disingenuous and misleading. Disingenuous because we have all been told that when Henry Cabot Lodge, running for Vice President on Richard Nixon's ticket in 1960, promised somebody somewhere that if Mr. Nixon were elected he would name a Negro to the Cabinet, Candidate Nixon almost fainted. And no wonder.

But how many Republicans and Democrats are having the same kind of conversation that we don't know about?

More from the Buckley column on general prejudice against black politicians:

The most frequently cited data intended to " document" American racial bias as it touches on politics are inconclusive. Congressman Dellums—and others— cite the presence in Congress of a mere thirteen black members of the House, and on e Senator. Why shouldn't there be—he asks—fifty black Congressmen, and ten Senators, reflecting the population figures?Once again, 1971 turns out to be a long time ago. There are now 19 black majority cities (Atlanta, New Orleans, Baltimore, Cleveland). But this is due to decade upon decade of black crime causing white flight. The population of Detroit, when blacks were a minority in 1970, was 1,514,063. In 2010, it was 713,777—but they’re represented in Congress by a black woman.Because, a) although there are 22 million blacks, the black population does not in fact exceed the white population in any single state, or in any single city except Washington, D. C., and Newark, New Jersey, and our political system is based on the single-member district, winner-take-all principle

Nixon’s deciding for political reasons not to allude—from the Oval Office—to the raw facts of race and IQ, or the equally raw facts about race and politics, is one thing. But Moynihan refusing to do so as an academic and public intellectual is another kettle of ethical fish.

The late Daniel Patrick Moynihan was a man who would frequently say something sensible about politics, and then quickly back, or possibly stumble, away. For example, the 1965 Moynihan Report (The Negro Family: The Case For National Action) couldn't be written today.

When a book of Moynihan's letters was reviewed by Steven Hayward at Claremont in 2011, I blogged about it, because what you get in a book of letters, like what you get from the Nixon tape above, are the things Moynihan was afraid to say in public:

As one would expect, Moynihan is more candid in private communications about certain delicate points than he chose to be in his speeches and published articles. In the 1970s, for example, Moynihan wrote publicly, "Liberalism faltered when it turned out it could not cope with truth," and contended the new political culture of the Left "rewarded the articulation of moral purpose more than the achievement of practical good." In his letters he was more accusatory, writing to E.J. Dionne in 1991, "The liberal project began to fail when it began to lie. That was the mid sixties...the rot set in and has continued since."We're still paying that “fearful price.” We’re paying for in terms of social policies, which, being based on the assumption of equality of intelligence, affect the victims of "reverse discrimination," and we’re paying for it in terms of how much affirmative action quotas cost businesses.Moynihan had raw personal reasons for feeling this way. As an assistant secretary of labor, he wrote the famous report in 1965 on the looming crisis of the black family. Both he and the report quickly became the objects of remarkably strident attacks that marked the beginning of political correctness—the willful, often enforced closing of minds to inconvenient topics and perspectives. (The denunciations grew louder four years later when Moynihan's "benign neglect" memo to Nixon was leaked to the press. It argued, quite sensibly, "We may need a period in which Negro progress continues and racial rhetoric fades."[PDF]) The author of the "Moynihan Report" noted in 1985 that because of the firestorm it occasioned, "a twenty year silence commenced in which almost no one worked on the subject [of race]." In another letter to an old colleague he added, "We have paid a fearful price for what American scholars in those years decided not to learn about."

Standing Pat, Claremont Review of Books, April 18, 2011 [PDF]. [Links and emphasis added.]

But Mr. Nixon’s Republican Party has also being paying for it in terms of how misguided “diversity outreach” and unelectable black Republican candidates affect party politics.

But Mr. Nixon’s Republican Party has also being paying for it in terms of how misguided “diversity outreach” and unelectable black Republican candidates affect party politics.

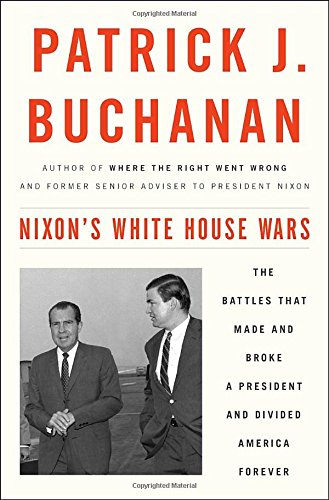

Pat Buchanan knew better on the political front—see his latest book on the Nixon White House, which led Joe Klein to call him “The First Trumpist” in the New York Times.

How much Trump knows about this stuff is something we can’t know—partly because it would cause riots.

But if public intellectuals and GOP politicians don’t get wise, it’s not going to be “morning in America”—but terrible night.

James Fulford [Email him] is a writer and editor for VDARE.com.

The Oval Office tape of Richard Nixon and Pat Moynihan posted on YouTube and recently noted by Steve Sailer has both men saying that they know the truth about IQ and race—but can never admit it. And look what happened as a result. VDARE.com’s position: the truth shall set us free.

The Oval Office tape of Richard Nixon and Pat Moynihan posted on YouTube and recently noted by Steve Sailer has both men saying that they know the truth about IQ and race—but can never admit it. And look what happened as a result. VDARE.com’s position: the truth shall set us free.